This article was originally published in ArabLit Quarterly: FOLK, in December 2021. The issue (and all the back catalogue up to the latest issue) can be purchased on Gumroad. A year since publication, and on the International Day for the Arabic Language, I thought it time to publish here for wider reading. This piece was an absolute pleasure to write, weaving family history, national history and folk poetry into one wider story. I hope you enjoy. ALQ remains the best way to read it and I highly recommend you purchase a copy of any issue – pdf, ebook or physical – if you enjoy this read. – Ali.

There are dark chapters in our history, under-documented but well known through the second-hand memories of oral retellings. I have learned some of this history by sitting with my grandmother as she recounted such stories. I say sitting with, although there were 3000 miles and a pandemic between us: me in Manchester, UK; she, in our village of Bani Jamra, Bahrain.

But through the mirrored screen of a smartphone, I did sit with her, and we talked for hours. The present pandemic receded as she recalled the past with me. “We repeated these words, but we never thought about their meaning,” she said between stories, “What did we know?”

Our family holds a strong oral knowledge of the difficulty of village life. Our village, Bani Jamra, lies on the northwest coast of Bahrain. Our collective memory is enhanced by the good fortune of having multiple poets in our lineage, particularly through my Granny Zahra’s paternal line. Memory, after all, is one of the main currencies of poets. And through these poems and stories, many memories are preserved from the time of serfdom, which our forebears lived through, and which ended less than a century ago, in 1923.

I already knew the stories of our male ancestors. There are the sons of Abdulrasool, whose many debts were used as a pretext by fidawis—the local lord’s thugs—to attack and arrest them. One son, Ali, fled with his family to Basra, while his elder brother Muhammad was dragged off to jail. In turn, Muhammad’s son Mansoor convinced the jailors to let him take his father’s place and serve the jail time. (Post-Publication addition: Both brothers, Ali and Muhammad, are ancestors of mine — Mansoor, my direct paternal ancestor, was father to my late grandfather Sheikh Abdulamir Al-Jamri)

Meanwhile, Ali’s family moved insecurely between southern Iraq and southwestern Iran. At one time, they lived together with Muhammad bin Salman, another migrant from the village, who fled after fidawis accused him of stealing the lord’s falcon. Their evidence was that a feather of the missing bird had been spotted on the roof of his weaver’s workshop. With the threat of violence above his head, he took his family northwards. Muhammad is also my ancestor, as his daughter married Ali’s son Atiyya. The couple married in Iraq and were my Granny Zahra’s paternal grandparents. (Post-Publication addition: Atiyya bin Ali would go on to become one of the greatest poets of the Baharna dialect)

These stories of migration aren’t just part of the legacy of my Bani Jamra family. They are common to the family and folk histories of Bahrain’s villages. On my mother’s side, there is the story of her great-grandfather, born into such great poverty at the turn of the 20th century that his family migrated to Qatar, where he remained until the 1930s. While I don’t know whether his family suffered injustices like those of my paternal ancestors, their poverty itself was a consequence of the harsh and arbitrary taxation levied on Baharna villagers.

Two systems called Raqabiyya (neck tax) and Sukhra (forced labour) defined serfdom in Bahrain. In essence, each lord could mistreat local village serfs without limits. An aristocrat could tax local villagers for anything they produced, or demand their labor in any way they wanted.

The most striking story of this violence in the village’s collective memory comes down from my Granny Zahra’s maternal grandfather, Sheikh Abdulla al-Arab. He and a friend were found murdered out on the road in 1923. They had been waylaid in the night on their return home from the capital, Manama. Sheikh Abdulla had become a loud campaigner for an end to serfdom and the arbitrary violence of lords, and he had rallied many of Bani Jamra’s villagers to petition against it. His death was a political assassination, an attempt to silence a prominent village Baharna voice and one of the final acts of violence that marked the end of that era. Even as teenagers in the 2000s, eighty years on, my cousins and I still recounted the story of his murder to each other.

The Baharna are settled Arabs, who trace their settlement in Bahrain and the surrounding coastline at least 1800 years back—with the name Bahrain referring to this larger geographic region. Their ancestry is tied to the ancient tribes of Rabe’a and Abdulqays, but also includes other Arab peoples who migrated, settled, and “Bahranized” over the centuries, adopting the Bahrani dialect and Shia faith that virtually all Baharna follow. The term “Baharna” was used as early as the 1200s, evidenced in nicknames and family names. Their lords, meanwhile, were from a much more recent wave of migration coming out of Najd; these Bedouin Arabs conquered their settled neighbors in the late 18th century, and their relationship in this period can be best described as one between conqueror and conquered. The Bahrani identity thus exists parallel to the Bahraini and other Khaleeji identities, and while these identities overlap in some respects, they contrast strongly in others.

The family histories passed down to me are political. My view of these endemic injustices was compounded by my readings, as a student, of Britain’s colonial India Office Records, which record detailed litanies of abuses the village Baharna presented to the British. They, having little power against the authorities, took advantage of the British’s destabilizing effect on the aristocratic status quo.

But missing across these stories are the experiences of women in their own voices. I know the histories of my male ancestors and can also read about them at length in colonial records. But it troubled me that I had no idea what the lives of my female ancestors were like.

I suspect two sources for my ignorance. The first is Arab patriarchal society: we value the stories of men over women, and it took me a long time to recognize and address this blind spot. The second was growing up in Britain during Bahrain’s 1990’s Intifada. The stories of our female ancestors appear regularly in folk stories and are passed from mothers, aunts, and grandmothers to their children, through the collective rearing of the community’s youth. But as I grew up in the diaspora, my mother had to compete with the homogenizing forces of Disney and Brothers Grimm, without the familial female network to back her up.

It took a pandemic for me to recognize the fragility of my knowledge and the sanctity of time spent together with family, but I finally—virtually—sat with my grandmother to hear her recount these folk poems. Through them, we escaped from the stillness of our present moment to a past both of us could only imagine. And while I rarely learned about specific women in our family (Granny Zahra often prefers to tell me stories of her father and grandfather), many of these songs and poems revolve around young girls and the dangers they faced in a time of feudal law, when they had fewer protections even than the men. In this way, an entire female community’s stories are preserved.

In her emptied-out majlis, usually so full of grandchildren and friends, platters of grilled fish and rice, trays of mixed nuts, generous portions of red tea and Arabic coffee, my grandmother relayed the poems to me.

| Fatima, our Fatamtam, our people’s springtime bloom. She went to sell our yoghurt, she went, now twelve days gone. Was she taken by a foreign man, or kidnapped by a lord? | فاطمة يا فطمطم يا ربيعة قوم راحت تبيع اللبن قعدت اثنى عشر يوم ما ادري خذوها عجم لو خذوها قوم |

This poem is vague enough to escape censorship, and among those Granny Zahra shared, it’s the only one I find included in modern collections of folk poems. But there is something deeply unsettling about it. I focus on the break in the -m rhyme in the third line, with the word “laban,” or yoghurt. This is the moment Fatamtam’s life changes, and the disruption of her kidnapping disrupts the children’s rhyme. Yet the -m rhyme is immediately restored in the following line with “yawm,” days. It is as though a stone, skipping across the waters, has unexpectedly sunk with barely a ripple left behind. There are local varieties of this poem from across Bahrain’s villages, with “yoghurt” sometimes optioned out for a different local product, such as yarn, and yet the ones I have seen all retain this disruption to the rhyme. That it could have been either a “foreign man” or a “lord” who is responsible heightens the ambiguity of the loss. And while ‘Ajam’ normally means Iranian in Bahrain, my opinion is that the word was chosen to work with the poem’s metre rather than to convey any deeper message about Ajam people. There is no closure, and it is not even clear who precisely is to blame.

“They said this about their lives,” exclaimed Granny Zahra after one poem, “expressing themselves in this way—in response to the darkness they lived through!”

Folk stories often deal in the morbid, communicating real dangers to children. So what does the kidnapping of Fatamtam tell us about the real dangers young girls faced? Under Raqabiyya and Sukhra, a lord could lay claim to any property or labor of their villagers. In a time when women were often treated as property, they, too, were at risk of such forced “acquisition.”

In the British records, there is a story of one aristocrat who was so well known for his forceful kidnapping of women that the villagers of his summer residence would annually send their daughters abroad, to family in Qatif (the other Baharna homeland on the mainland, what is today’s Eastern Province in Saudi Arabia). Fatima was then and remains today a very popular name amongst the Shia villagers. There were Fatimas around the islands at risk of this same, ambiguous fate.

While Fatamtam’s poem is recalled around the islands, there are others that are much more local. Granny Zahra relayed another known only to our village:

| Have you seen Sabbagh’s young girls? (They said no) Kohl-lined eyes and egg-white skin? (They said no) Wearing bakhnags, woven green? (They said no) Dragged off by a bedouin? (They said no) Taken to the Sultan’s son? (They said no) Can my heart strings be restrung? (They said no) I turn to God for mercy! (They said no) I’m left sick with misery! (They said no) (They said no) (They said no) (They said no) | ما شفتون بنات الصباغ قالوا لا مكحلين و بيضان قالوا لا عليهم بخانق خضران قالوا لا خذوهم مني البدوان قالوا لا ودوهم لابن السلطان قالوا لا قطعوا مني النيطان قالوا لا أشكوهم ربي الرحمن قالوا لا داووني بدوا الصرعان قالوا لا قالوا لا قالوا لا |

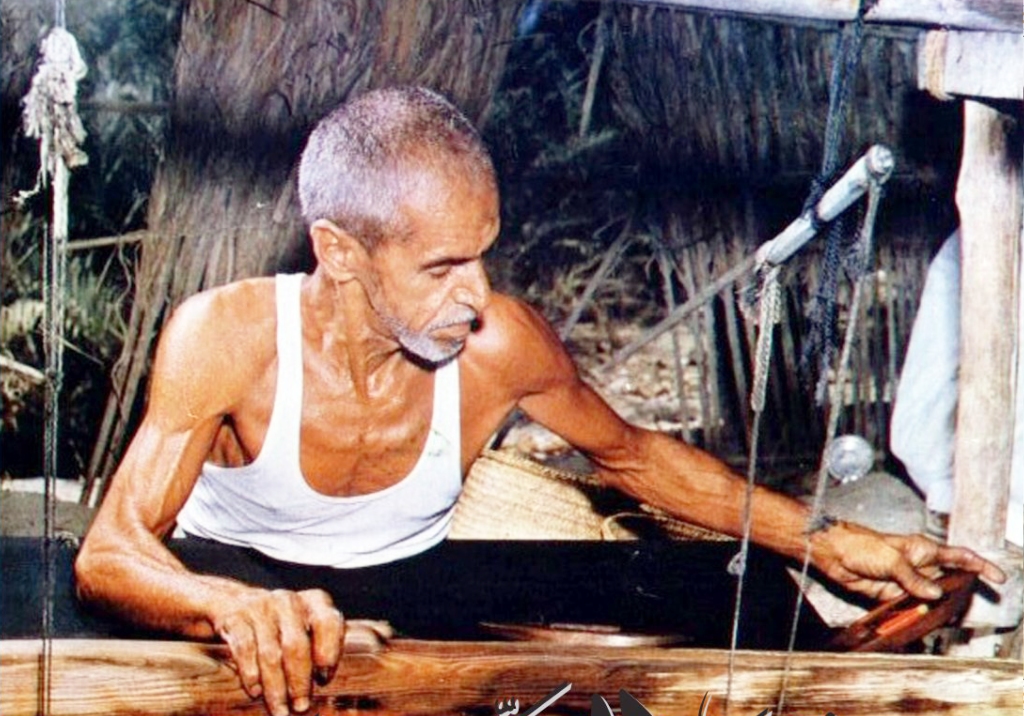

Wrapped in a light green cloth and wearing sunglasses even indoors, Granny Zahra stroked her chin as she relayed the story of this poem. It is said that, in the old days, Al-Sabbagh was a weaver, as so many of Bani Jamra’s men were:

“He worked in his shop, and he had two young daughters who sat by him. When a client comes, he sends them to bring coffee and dates—or rutb if it’s the season. One day, a man comes on his horse and visits his workshop. Al-Sabbagh tells his daughters, go bring the dates. One comes carrying the coffee pot, the other comes with the basket of dates. One of those old, lovely, woven baskets, not like today’s nylon things, no. So they come with the goods, and each of them is wearing a green bukhnag.”

Here she got up to dig out an old bukhnag and held it up in front of her. A clothing for young girls, the dress envelopes the upper body and head, so that the girl’s face is like a moon over a field of embroidery. She continued:

“The client sees how pretty they are and says, ‘Are these your daughters?’

“Al-Sabbagh says, ‘Yes, long may your life be, so they are.’

“The client replies, ‘Well, now they are mine.’ He finishes the coffee, lifts the girls onto his horse and goes off with them. Al-Sabbagh could say nothing, the impoverished man. He went mad! He closed his workshop down and went banging on all the doors.

“‘Have you seen Al-Sabbagh’s girls? They said no’ – he replied to himself! ‘Kohl-lined eyes and egg-white skin? They said no. Wearing bakhnags, woven green? They said no.’ Always replying to himself! He went mad—there was nothing left for him. He could no longer weave, he just went around asking after his daughters. It seems he had no other children but those two girls, still just so young.”

The descent to madness is captured in the poem. From his descriptions first of his young girls, then of their kidnapper (there was no Sultan in reality, so the word may be taken to indicate a noble). Then he turns within—with a plea to God—before a descent into the repetitive madness of They said no. Al-Sabbagh said nothing as his daughters were taken, and now in his poem he seems to be externalizing his own silence. Did he feel complicit in their kidnapping? But what could he have done? Under Raqabiyya and Sukhra, a lord was entitled to anything from the villagers—including their people. The dangers for a parent who put up a fight were real.

These poems speak both to the grim danger young girls faced and the lack of agency of their guardian adults. One of the most disquieting stories I read was discovered unexpectedly in Mahdi Abdulla Al-Tajir’s Language and Linguistic Origins in Bahrain: The Baharna Dialect of Arabic (1989). Tucked in the annexes of this linguistic study is an interview with a woman from Duraz, a village neighboring Bani Jamra. She relayed this folk tale to Al-Tajir, and I have reproduced the text, slightly amended for readability:

Once upon a time there lived a man, he was a ruler—there is no ruler but God! Near his house there was a hut which belonged to his poor neighbor. The owner of the hut had a small garden, according to his limited means. It was very hot that night. The Sultan, the ruler, said, “Let us go to the poor man’s garden for a short walk.” They went out for a walk.

Suddenly, there were two persons standing, one with a piece of paper and a pen.

One said, “Write, brother!”

The other answered, “What should I write?”

He said, “Write down that the Sultan’s wife will conceive and will give birth to a boy, and the wife of the poor man will conceive and will give birth to a girl, and they will get married. The poor man’s daughter will get married to the rich man’s son.”

The Sultan kept what he had heard to himself, and he went home. God decreed, and the Sultan’s wife conceived and gave birth to a boy and the poor man’s wife gave birth to a girl. It happened as the voices predicted.

As soon as he knew of the poor man’s wife giving birth to a girl, he went to her father and said to him, “A girl was born to you.”

The poor man replied, “Yes, a girl was born to me.”

The Sultan said, “Sell her to us.”

The man said, “Why should I sell her to you? If I agreed to do so, her mother wouldn’t.”

The Sultan said, “No, you should persuade her. I shall give you this much money…”

So the man went to his wife and said “Oh! Daughter of so-and-so, the Sultan says he wants to buy our daughter. Shall we sell her to him? What is your opinion?”

She exclaimed, “Yuu! She is a new-born babe! She is young, we couldn’t sell her!”

“I am telling you to give her to him,” he said, “or they will kill us.”

The Sultan’s men came and she was given to them. She was given to them… what the Sultan did was that he took her in her wrappers to the forest, where dogs live. Near a grave, he disembowelled the girl and ran away.

That day, the girl’s parents were going to their garden. The mother heard somebody breathing in the forest. So she said to her husband, “Do you hear anybody breathing in the forest?”

“Perhaps,” he replied, “a bitch has given birth and these are her puppies.”

She replied, “No… and I am not going to budge from here unless you accompany me.”

When they entered, they found their daughter lying in the forest, still breathing, with her stomach cut open.

They took her home and nursed her wounds. The wound healed.

The father said, “Daughter of so-and-so.”

The wife answered, “Yes.”

He said, “What is your opinion?”

“Regarding what?” she answered.

“Let us leave this country,” he said, “we don’t need it any longer. If this is the beginning, the end is surely worse! Let us go abroad.”

They travelled. Where did they go? They went to Basra.

The folk story gives no explanation for the Sultan’s brutal actions, though we can make guesses. That reflects, I think, the social chasm between the lords and their serfs who spun these stories. Interestingly, the Sultan’s arbitrary violence is also a rejection of a prophecy. In so doing, his actions are not just against the villagers, but also against the divine. The prophesied marriage remains unfulfilled by the end of story, and, as with the break in Fatamtam’s rhyme, the unresolved plot point reflects the severe disruption to life caused by this casual violence against women.

The stories of Fatamtam and Al-Sabbagh’s girls convey the real danger facing young village girls —most shocking about this story is just how young the unnamed girl is. There is a silver lining, with the parents managing to save their daughter and making the one choice they have agency to make—to leave for Basra.

The folk story’s ending suggests the late 19th and early 20th century, when Baharna migration from their villages to safe havens in the Gulf was so common, with Basra often being the first port of call. And there is a truth in it. Granny Zahra’s paternal grandparents married in Basra, where their own parents had fled to escape such arbitrary violence. The girls in these stories are thus both real and imaginary. How many of these folktales may reflect the real experiences of my female ancestors?

“Poor things. Even your grandmother,” said Granny Zahra to one of her sons, “would say they had to flee at times from these people coming to beat them.”

I shudder to imagine these things. Yet while so many of the poems capture ambiguous loss, violence, and stripped agency, the act of telling and retelling them becomes an act of resistance. Children could be kidnapped and exploited, parents could be imprisoned, but people would not forget.

The clearest example of this comes in my favorite poem from this period:

| Speak, my ceiling of date palm bark, Have you seen Afifa Have you seen Latifa? They have taken my health And they have taken my wealth And as they left they shat on the bedspread! Once they were my highest heights, And once, my greatest glory, But they’ve dropped me to deep depths— So gather round, family, find me a solution, For my house smells like a carcass And I may as well be dead. Tell me, tell me truly— Were they gobbled by a sa’loo, Or do they roll in another’s bed? | يا جدوع البيت ما شفتوا عفيفة ولطيفة؟ أخذوا حالي ومالي وزقوا في الصريفة ودوني العلالي ودقوا بي حسافة يا هلي وعيالي شوفوا لي تصريفة عمري صابه البين وداري صارت جيفة مادري كلهم سعلو لو لفوا صريفة |

What a relief from all the gloom! A victory for two of these girls. I received the poem from a different source, but when I read it out to her, Granny Zahra’s laughter crackled through the phone, and she repeated the familiar lines back to me.

Unlike our previous poems, this one is told in the voice of the aristocrat. As such, it mimics the ‘Anizi dialect spoken by people of Bedouin descent, quite distinct from the Baharna dialect that the other poems are relayed in. This lord lacks dignity and sanity. He cannot understand why Afifa and Latifa have run away—from his perspective, surely he had doted on them? He wonders whether a sa’loo—a demonic wolf creature—had eaten them, or if they’ve found another man (or rather, another man had found them). His home has been left like a corpse. And why wouldn’t it be? Afifa and Latifa have left a stinky goodbye present. Does he deserve anything more?

The reality for women and girls would have been grim. Even if they escaped their captivity, their return to the patriarchal society of the village would be difficult. But we can celebrate this moment, when the two strong-willed girls escape. This vulgar comedy allows the villagers to humiliate the lord, and where Fatamtam has been lost, Afifa and Latifa are saved, and this time, there’s no ambiguity to the fact that they were active participants in their own fate. In my own search for closure within this journey, I like to imagine that Afifa and Latifa are Al-Sabbagh’s girls. Why not?

Granny Zahra’s mother, Salma, was just a year old when her father Abdulla al-Arab was murdered in the course of his campaigns for an end to serfdom. Though he didn’t live to see it, his work was successful. British interventionism in Bahrain was intensifying in the early 1920’s. The Baharna villagers, who had been powerless under the old regime, took advantage of the situation, lobbying the colonial force for an end to serfdom, which became the major political issue of its day. In 1923, the colonial power forced the abdication of the ruler—this was much more about imperial interests than any moral objection—and put his more compliant son in power. Under new leadership, Bahrain abolished the practices of Raqabiyya and Sukhra, and with them, serfdom. As a result, Salma never experienced the things her foremothers did. While it seems some threat remained in her day, it was not comparable to the arbitrary violence and risk women faced before.

Life for that first generation after serfdom’s end was neither simple nor straightforward. As Granny Zahra tells me, “Everyone in the villages lived in great poverty. Especially the ones from the farming villages—Bani Jamra and Duraz had it a bit better, while the farms had it worse.” As she talks about the period just before her birth in the 1940’s, the tales are full of lice, dirt, and hunger—but not of the threat of arbitrary violence that characterised her grandparents’ generation. Her mother Salma would have heard the stories of the women that came before her, and passed them on to her own daughters, who have passed them on again.

With each retelling, we remember. But why should we remember such terrible things? There are plenty of folk songs out there with less darkness in them, ones that capture a gentler childhood innocence. But these are compelling. From a young age, these stories prepare children for the social injustices they may one day face. And in their retelling, they capture another truth—that expressing these stories relieves the storyteller’s burden of suffering. The retelling is itself an act of resistance.

In turn, it roots us in our environment and our history, and allows us to understand our place in the world. During the pandemic, unable to visit my family, folk tales and oral histories became our way of passing valuable family time. Through remembering, we can reflect on a time now, thankfully, very much in the past, and we can consider what has changed for the descendants of those villagers, and also what has not.